Li-Fi on board

Our appetite for data is continuing to grow, which requires looking for alternatives beyond the traditional Wi-Fi technologies. Experts have a bright idea: why not access the internet through light bulbs? And not just at home, but also on a plane at an altitude of 10,000 metres.

The sound that reminds us of the early days of the internet goes something like this: first, there’s a dialling noise, followed by a long beep and then a scratchy chrrrzzzzz. It’s the dial-up sound of a 56 k modem (listen to it at savethesounds.info). In the ‘90s, this was the odd noise you heard every time you connected to the internet over the telephone line.

Those who experienced it at the time remember it well – although perhaps with mixed feelings. After all, while the internet modem opened the door to the World Wide Web – a novelty at the time – the web pages were painfully slow to load. If you wanted to download a music file, you were best advised to grab a good book to keep you occupied during the long wait.

Thankfully, this is a thing of the past. With Wi-Fi, today’s internet is 100 to 200 times faster than in the days of the 56 k modem. Experts around the world are working on 5G, the next generation of wireless broadband technology, to provide faster speeds, lower latency and better coverage than the current 4G technology.

It seems there will be no limits to the internet of tomorrow. However, according to Harald Haas, Professor of Mobile Communications at the University of Edinburgh, there’s a problem: “The radio waves currently used for transmitting data are limited, and we are beginning to run out of spectrum,” he says. The problem is compounded by our ever-growing and voracious appetite for data.

According to a prognosis made by Business Intelligence, the number of items connected to the internet will amount to 24 billion by 2020. Add to that the 10 billion smartphones, tablets, smartwatches and other gadgets, and a total of 34 billion devices will be connected to the World Wide Web by 2020 and able to communicate with each other.

Accessing the internet via light

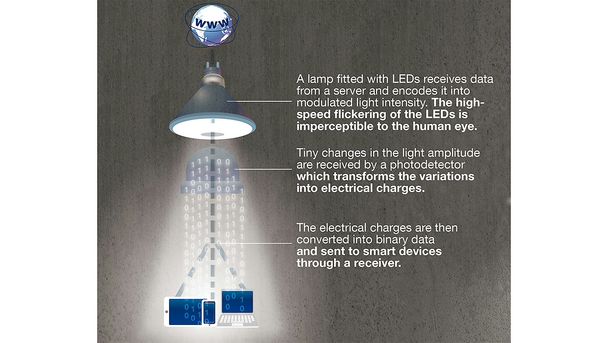

As a suggested solution, the researcher presented his vision of accessing the internet via light, or Li-Fi, during a TED Talk in 2011. Using the technology, data is transmitted by changing the light intensity of LEDs at such a high rate that the flickering of the light is not visible to the human eye. A light sensor on the end device – for example a laptop – receives the data transmitted by the flashing and dimming light.

“The vision is that all we’d need to do is fit a small microchip to every illumination device to turn street lamps, office lights and bedside lamps into Li-Fi hotspots,” explains Haas. As there is a lot more visible light spectrum available than radio wave spectrum, it could be used to achieve higher data transmission speeds.

During experiments, scientists have already achieved speeds of 15 gigabits per second (Gbps) and have shown that future light bulbs can transmit 100 Gbps. At that rate, you could download 12 high-definition films in 60 seconds. Data transmission is even possible when the light is dimmed to levels hardly perceptible to the human eye.

Integrating Li-Fi on board

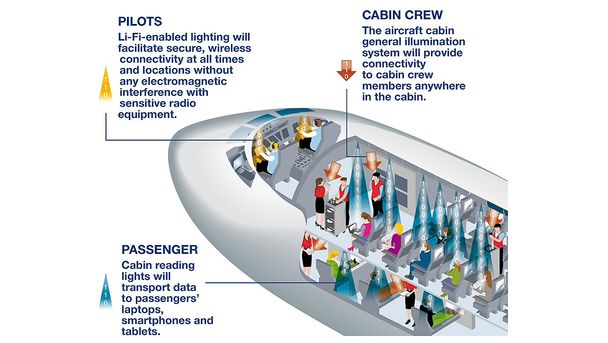

According to Haas, all of these aspects make aircraft an ideal place to use Li-Fi. Each reading light in the cabin could easily be fitted with Li-Fi technology and turned into a hotspot, which would provide passengers with a sufficient volume of data to stream videos or immerse themselves in digital worlds.

So it’s no surprise that Haas’s vision has drawn a lot of attention – including at Airbus. “The first time I saw Professor Haas’s TED Talk, I just had to meet him,” explains Eric Peyrucain from Airbus’ Digital Transformation Office.

For this reason, Airbus has been in contact with Haas over the last few years paying special attention to the advances he has made. With his company pureLiFi, Haas has, for example, developed the world’s first Li-Fi dongle that connects to mobile devices. In 2011, the prototype he presented at a TED Talk was as large as a lectern. Today, it is the size of a business card, and within the next two years it is set to become small enough to fit into smartphones and tablets.

Airbus, however, has no intention of waiting until Li-Fi has entered the mass market. Developers are already working on solutions to integrate the technology on board.

Airbus is also working on solutions to give the cockpit Li-Fi access, explains Valentin Kretzschmar, aircraft data specialist at Airbus. The problem isn’t a new one: aircraft have an array of cables that add a great deal of dead weight. While Wi-Fi could solve this problem, it cannot be implemented without careful consideration.

Li-Fi, on the other hand, is safer, as it is not transmitted through walls like Wi-Fi and is therefore harder to tap from outside. This would, for example, make it much easier to prevent data streams in the cockpit from being hacked into from the cabin than if Wi-Fi were used.

"We don’t want data streams in our offices to be hacked from outside either, and Li-Fi provides a unique solution, since the signal isn’t transmitted through walls”, says Eric Peyrucain.

According to Peyrucain, the potential applications of Li-Fi at Airbus are not limited to aircraft. “We also see great potential for our manufacturing facilities.” Others have also seen the light: numerous companies and organisations such as the LiFi Research and Development Centre at the University of Edinburgh, the Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft and NASA are driving the development of Li-Fi, a strong indicator that the Li-Fi vision will become reality. 20 years ago we accessed the internet at home with beeping modems. Now we are surfing silently, wirelessly, and soon, maybe, using light.

Beata Cece