Meet Refilwe Ledwaba, the first Black female helicopter pilot in South Africa

Refilwe Ledwaba is a social entrepreneur, fixed-wing and helicopter pilot and a PhD candidate. She is the first Black woman to become a helicopter pilot in South Africa.

Ledwaba founded the Girls Fly Programme in Africa (GFPA) Foundation in 2009 to encourage more girls and women to enter careers in Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics (STEAM).

When did you realise that you wanted to become a helicopter pilot?

It was actually during my first flight in a helicopter! I grew up in a semi-rural area, and the closest I had seen a pilot was on TV. I didn’t know that women could become pilots, or even that Black people could become pilots. I finished university with a Bachelor of Science, majoring in biochemistry and biology and I found myself applying for a job at an airline as a cabin attendant.

That’s when I realised there was this whole new world I didn’t know about, and I started taking flying lessons. I was flying and working at the same time. The initial plan was that afterwards, I would go back to university and study to become a doctor, but after discovering aviation, I wasn’t so keen on becoming a doctor anymore. I wanted to become a pilot.

Could you tell us about the challenges you had to face at that time?

Flying was really expensive. I was able to afford a one-hour flying lesson a month, and I needed about 200 hours to actually get my commercial license. I realised it was going to take me years, so I started writing letters to every company I knew, explaining who I was and why I was interested in flying. I also wrote that I wanted to give back to my community, and inform the children there, to tell them that there is a beautiful industry that we can be a part of. The South African Police Service responded. My initial plan was to stay with the SAPS for two years, but I ended up flying with them for 10 years. The first flight in a helicopter was just so amazing!

What were your missions with the SAPS?

We had exciting missions, as we were based in KwaZulu-Natal, with the mountains and the ocean right next to us. My favorite operations were mountain-flying. Rescue flights in the mountains are challenging, as they require a high awareness of your environment. The wind can change really quickly, and you also have to complete one of the most difficult operations with a helicopter: hoist. Whenever we performed a rescue mission with the SAPS, we always made sure to land near a neighbouring school on our way back, in order to engage with the communities around us.

How has your upbringing influenced your mindset as a woman in aviation?

I was very privileged to grow up in a community with remarkable women: my mother raised seven kids, and she was one of the first female school principals during apartheid in South Africa. Women in my community were doing amazing things, and because of this particular mindset and freedom, as a woman I knew that I could do everything. To me, it was normal for women to be educated, for women to be as powerful as men, and for women to give back to their community, because that’s what we do: we lift as we rise.

Did you expect it to be a difficult path to follow?

I only realised that I was the first Black woman with a commercial helicopter license in South Africa when I received my wings. That’s when I picked up that I was actually doing something people weren’t expecting me to do. Being the first can weigh in on your mental health, but I was lucky to receive strong support from the people who trained me at SAPS, and this helped me overcome the challenges I encountered. For example, according to the flying regulations at that time, I didn’t weigh enough to fly a helicopter solo. But my instructor encouraged me to find a solution rather than quit straight away. We added sandbags in the helicopter so that I could complete my flight hours, and it became a joke between us, because I was always carrying a sandbag before flying. I think it’s a good example of the power of mentoring, and the impact it can have on young people: everyone needs someone who is here to cheer them on and show them what they can accomplish.

To me, it was normal for women to be educated, for women to be as powerful as men, and for women to give back to their community, because that’s what we do: we lift as we rise.

Refilwe Ledwaba

How did this experience shape the Girls Fly Programme in Africa?

The way we built the GFPA was partly based on my personal experience, because if I hadn’t received all this support from my mentors, there is no way I could have achieved this career. We made sure to engage with different communities, by creating a platform where women can come together and discuss the challenges they face. The programmes also include young boys, because they are part of the solution to normalise women entering a career in aviation. Imagine these kids having a female astronaut visit their school and help them code on computers: this will have a huge impact on how they behave in the workplace, because they grew up in a system where boys and girls coexist and can have the same opportunities.

How are the programmes designed?

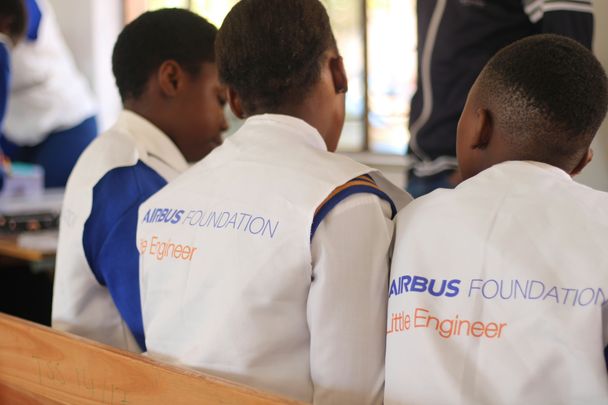

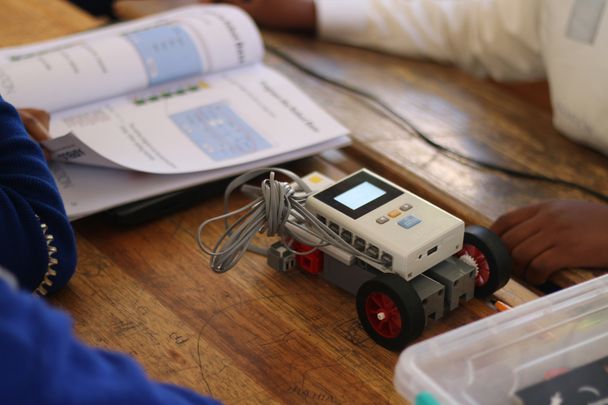

First, we inform kids in schools about the career opportunities in aviation, by organising visits and talks with women in the industry. Then we start a streamlining phase, to know who is interested in STEAM and would like to participate in the workshops we offer, such as Airbus’ Little Engineer, using robotics, coding and design thinking to have them practice the skills they will need in this field. In the third phase, we reach out to our sponsors and get the kids involved in scholarships, job shadowing and internship opportunities, to give them access to all the possibilities. We have seen very great outcomes so far, as a lot of our girls who started the programme when they were in grade eleven are now getting jobs as aerospace engineers.

What’s next for the GFPA?

The next step for us is scaling up as a foundation to increase our impact: we are currently present in South Africa, Botswana, Ghana and Kenya, but we’d like to launch other initiatives in new countries and adapt them to the challenges kids are facing there. We are looking forward to what the future will bring for the GFPA!

This interview wouldn’t have been possible without the precious help of Lynne Carstens.